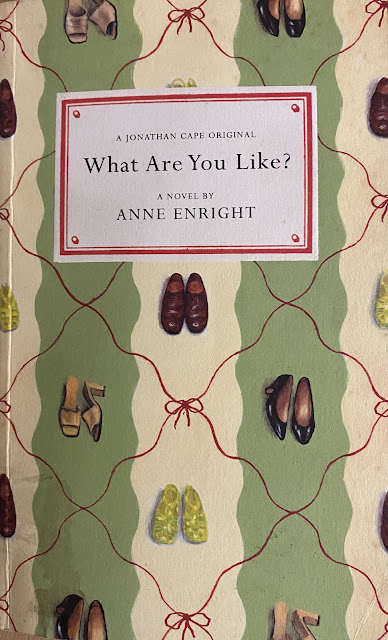

What Are You Like?

By Anne Enright

(Jonathan Cape, p/b, £10)

The colloquial, jokey inquiry, usually delivered when someone has done something unbelievable stupid, takes on a more sinister undertow in the title of Anne Enright’s fine new novel, as do many other casual phrases and situations we tend to take for granted in the everyday world. But then doubling, or a second thought bifurcating out of a first one, giving two thoughts at the same time (which is what a pun is), is integral to this work, no more so than in the fact that we have twin heroines, Maria and Rose, separated at birth and unaware of each other’s existence. The story alternates between Maria in New York, Rose in London, stopping off now and then at the home of their father Berts and his second wife Evelyn in Dublin, their mother having died when they were born, until the denouement, when all comes together.

If shifting constructs of identity, and its ultimately arbitrary nature, are what preoccupy Mary Morrissy in The Pretender, so too do they intrigue Enright, and both women’s vision operates in a more personal, and therefore more universal way than the irritatingly narrow focus on post-colonial Irish identity we hear so much about from the Irish Studies Departments of universities, in their study of Irish literature (i.e. literature made by people who were born or live in Ireland). Indeed, the only place where Enright’s formally fluid and capacious book goes a little awry is in a section called ‘The Abortionist’s Restaurant’, where Rose ponders on her Irish identity, or lack of it. This reads like a graft that didn’t quite take, as though included as a sop to the academies, and is the only time when Enright’s cleverness and imagination become a trifle heavy-handed, instead of being both light and profound. When we read Gabriel Garcia Marquez, are we worrying about Columbian national identity?

The twin motif has long appealed to the more metaphysical of minds, providing as it does an image of a lost self, or future, uncreated self, so that the self is not quite whole, or is not the whole self, which amounts to almost the same thing. Mistaken identities, and their resolution, often across class and gender lines, are a staple of Boccaccio and Chaucer, and were often filched wholesale by Shakespeare. Nabokov delights in it, and it is central to Banville’s Birchwood and Mephisto. Scottish writer Ali Smith covered recognisably similar philosophical territory, although concerning friends rather than twins, in her novel entitled, with succinct appropriateness, Like. But similarity is not identity.

Although not plot driven, what happens is that when Maria turns twenty, she falls in love, in the wrong city, with the wrong sort of man. Going through his things, she finds a photo of herself when she was twelve years old. She has the same smile, but she is wearing clothes she never had: she is the same, only different. Stepping through the mirror to tell the story of two women, both haunted by their missing selves, both unable to settle in their first choice vocations of engineering and musicianship, What Are You Like? is a deftly written disquisition on families and - dread word - identity. In its choice of topos, it takes on an almost mythic resonance. Coincidentally, again like Morrissy, it includes a revealing passage from a dead woman in her grave.

Perhaps the quirky, incongruous, oblique style favoured by Enright, and her Irish contemporary Aidan Mathews, is more suited to shorter forms, rather than full-length novels, just as they were more successful vehicles for someone who must surely be one of their mentors, Donald Barthelme, than were some of his longer prose works. What Are You Like? marks an advance on Enright’s somewhat airy 1995 novel, The Wig My Father Wore, but the eloquently laconic voice of the stories in the 1991 Rooney Prize winning collection The Portable Virgin still rings true with most assurance. But it’s novels that matter these days, apparently. However, writers from Lawrence Sterne to Flann O’Brien have shown that straight ahead narrative is not the only game in town when it comes to longer forms, and this is a noble tradition which it is to be sincerely hoped that Enright has the courage to persist in pursuing. It certainly makes a change from ninety percent of the material which passes for challenging new Irish fiction at the present time.

First published in Books Ireland

No comments:

Post a Comment