Marilyn and Me

By Ji-min Lee

(4thEstate)

The Korean War (1950-1953) is commonly referred to in the Anglophone world as ‘The Forgotten War’, which apart from the more obvious question ‘Why?’, also prompts the query ‘By whom?’

The ‘Why?’ has several credible explanations, foremost among which is that, sandwiched between the euphoric rectitude of the ‘Just War’ victory over the forces of evil in World War II, and the nadir of the moral bankruptcy and humiliation of ‘The War That Wasn’t Won’ of Vietnam, the Korean hostilities have been consigned to a footnote in American history. This is to underestimate grossly its importance: not only as the first major conflict and carve-up along Cold War lines, which still resonates today in the Trump administration’s agitation over North Korea’s nuclear capability; but also because of the sheer devastation it caused the war-torn country. Between three and four million people lost their lives, as many as 70% of whom were civilians. Destruction was particularly acute in the North, which was subjected to over two years of sustained American bombing, including the first use of napalm. Roughly 25% of Korea’s prewar population was killed. Damage was also widespread in the South, where Seoul changed hands four times. Furthermore, technically, the war has never ended: the fighting stopped when North Korea, China and the U.S. reached an armistice in 1953, but South Korea did not agree to it, and no formal peace treaty was ever signed. Ironically, the Forgotten War is still going on.

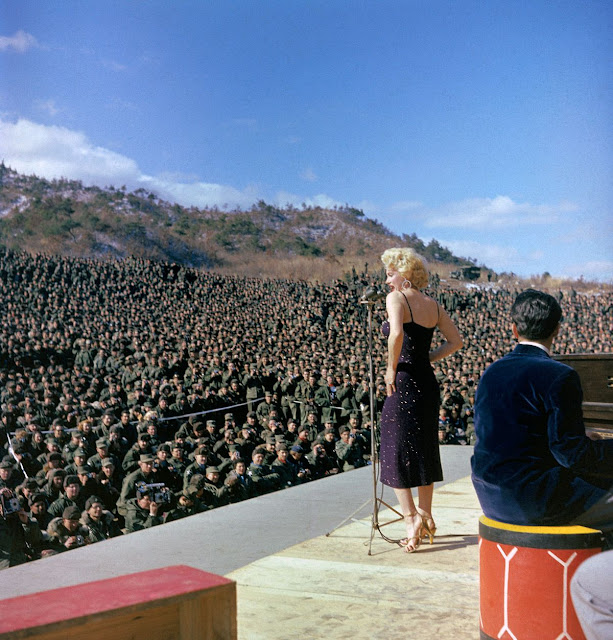

As for the ‘By whom?’, it would appear the answer is ‘Everyone, except the North Koreans.’ Largely elided from American historical discourse, and too painful to be passed on to younger generations of South Koreans by those who survived, in the popular consciousness the most significant fact about the Korean War is that for four days in 1954, Marilyn Monroe entertained American troops stationed there.

All of which preamble is only important for our purposes here because this war and its aftermath is the world inhabited by the heroine and first-person narrator of this novel, Alice J. Kim – real name Kim Ae-sun. The novel opens in Seoul in February 1954, just over six months after the armistice, but with military tensions still high, American troops present in force, and the country itself completely devastated. Alice, now in her late twenties, who was an artist and something of an intellectual before life-altering events overtook her during the war, is working as a typist on the U.S. base, where she is the only Korean woman making a living off the American military without being a prostitute – although everyone assumes that she is. ‘Only whores or spies take on an easy to pronounce foreign name.’

With Japan’s surrender to America at the end of WWII, America occupied the ex-Japanese colony of Korea, but for Alice, ‘Everything remained the same, except the flag flying in front of the former Japanese Government General of Korea building had changed from the Japanese flag to the American one.’ This observation should find resonance locally, where we are often told that the only change in post-Independence Ireland was that postboxes changed colour from red to green.

When Marilyn Monroe takes time out from her Japanese honeymoon with Joe DiMaggio to tour Korea, Alice is selected as her translator, because of her trilingual skills. With her prematurely grey hair which she dyes with beer, her fraying lace gloves that hide (self-inflicted) burn marks on her hands, and the memories she fears will engulf her, Alice is – in contemporary parlance – suffering from PTSD, and so initially subdued in the presence of the famous Hollywood starlet. ‘War had killed the love and hope and warmth within me, but it had also spared me. I covered my face with my hands, sobbing out the last bit of love to shore up the life remaining inside.’ But as these two women form an unlikely, temporary friendship, the story of Alice’s traumatic experiences in the conflict emerges, and when she becomes embroiled in a sting operation involving the entrapment of a Communist spy she is forced to confront the past she has been trying so hard to repress.

The narrative alternates between 1954 and the years 1947-50, and much of Alice’s current suffering is related to her pre-war, personal love life. Her two ex-lovers, who reappear in her post-war present, are married writer Yo Min-Hwan, and Joseph Pines, an American spy posing as a missionary. They form a naïve ménage a trois, which ends abruptly when she betrays one with the other. But she is also haunted by her failure to protect two little girls in her charge during the strife, Yo’s daughter Song-ha, and Chong-nim, an orphan ‘who grabbed my hand trustingly as we escaped Hungnam amid ten thousand screaming refugees.’

Alice is a suicide survivor who is planning another attempt, but who comes to realise before it is too late that she is not necessarily responsible for the survivor guilt which is crippling her. Obviously written with an eye to possible filmisation (Lee is a successful screenwriter in her native country), hardly a word is wasted in this beautifully written short novel, especially during the early scene-setting sections. However, the cathartic effects, delineated in the denouement, of Alice’s time with Marilyn, are at best tenuous and at worst contrived. It is telling that the only way to get a Western audience interested in a neglected international episode in which the West was involved, is to drag in one of its most legendary cultural icons, kicking and screaming, rather than focusing solely on the validity of an indigenous woman’s experiences. But maybe that was a calculated compromise, deemed judicious. The work is, nevertheless, a necessary and timely act of reclamation and remembrance for the so-called Forgotten War.

First published in The Irish Times, 27/07/2019