Wednesday, 30 December 2020

Favourite Books #30

Friday, 11 December 2020

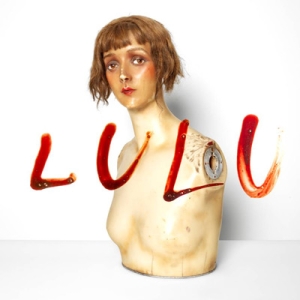

Lou Reed & Metallica - Lulu

Wednesday, 2 December 2020

Favourite Books #29

Watching recently The Plot Against America, David Simon’s and Ed Burns’ excellent TV series adaptation of Philip Roth’s 2004 novel of American alt-history, reminded me of the rich vein of form that Roth hit at the turn of the century, including the loose trilogy American Pastoral (1997), I Married a Communist (1998) and The Human Stain (2000). Reading these books, I get the same feeling I get as when I listen to an album like John Cale’s and Lou Reed’s Songs For Drella: this guy knows how to write a novel, just as these musician/songwriters know how to make a record. They’ve been doing it all their lives. They know how these things work. No matter how complicated the work may get, there is an internal structure and simplicity to them that carries them through.

The Human Stain is another novel I used to teach. We always came back to the same question: is there something noble in Coleman Silk’s defiance, or is he just an arrogant old white (heh!) male, past his sell-by date? Maybe both…

Wednesday, 11 November 2020

Favourite Books #28

Monday, 9 November 2020

The Queen's Gambit

I know it’s been dissed a bit in some quarters, but I thoroughly enjoyed The Queen’s Gambit. I can see that it starts out brilliantly and finishes up rather conventionally, and maybe there was not enough story to sustain 7 x one hour episodes. But who cares, when the production values are so high, the design so beautiful, and it looks so good? Yes, Anya Taylor-Joy may spend a lot of time later on swanning around looking glamourous until it appears her character Elizabeth Harmon is serving as nothing more than an elegant clothes-horse for expensive fashion items, and her easy defeats of opponents may become a bit predictable (although she encounters tougher challenges as she reaches the summit), but I was still rooting for her all the way – especially in the heavily male-dominated world of competitive chess. Besides, her glamour is just a critique of the notion that a woman can’t be super smart and a knockout at the same time (a criticism addressed in her relationship with French model Cleo anyway). Look, I just plain liked the fact that the whole series stood on its head the often geeky, nerdy, buttoned-up image of high-level chess, and managed the not inconsiderable achievement of making chess look sexy. And I know that’s a bit like praising immaculate record production when the songs are naff, but in this case the material is not, in my opinion, naff at all.

So many things I liked: the subtlety with which her amorous relationships with men (and women) were handled, everything understated; the Cold War atmosphere, which EH effectively disrupts in how she behaves after her triumph in Russia; the perfectly captured sense of stifling domesticity and thwarted ambition women suffered under in the ’50s, personified in the character of stepmom Alma (and also EH’s own birth mother); EH telling the good ladies of the Christian organisation which has been sponsoring her to take a hike when they want to use her as a propaganda tool – why? “Because it’s fucking nonsense?” (note the raised, interrogative, intonation); the sense it conveyed of what many top players – solitary, obsessive types – have spoken of as the appeal of chess, that they feel safe when playing, because it reduces the outside world to the sixty-four self-contained squares on the board. Finally, who doesn’t like a story of an orphan making their way in the world, overcoming adversity when the odds are stacked against them?

I’m no grandmaster (in fact, I’d be one of the amateurish guys Elizabeth Harmon would have blown away with bored, dismissive ease at the start of her career), but maybe you just need a passing interest in and appreciation of the game in order to fully enter into the JOY of the series. I could have watched it all day – and night. My kind of girl (although of course she’d break my proverbial heart).

Thursday, 5 November 2020

Favourite Books #27

And we think the postmodern novel came along sometime after the Second World War? Think again. First published serially between 1759 and 1767, Tristram Shandy remains as unconventional now as it was then. It gives us little of the life, and few of the opinions of its writer/protagonist, the hapless Tristram. Hell, he doesn’t even manage to get himself born until Volume III, and the story terminates when he is four. He realises he will never have enough time in the rest of his life to tell the story of his life, so prone is he to digression and exactitude. He is engaged in a race against time which he is bound to lose, if it takes him a year to write about a day in his life. “A COCK and a BULL – and one of the best of its kind I ever heard.”

Wednesday, 28 October 2020

Favourite Books #26

During the first lockdown in March (ah! those halcyon days!) my friend Deirdre Irvine, owner of The Open Window Gallery in Rathmines, kindly asked me to post the covers of 7 books, with no reviews, as part of a challenge to create a library of great classics. Deirdre wrote: ‘It was difficult choosing one book over another and leaving swathes of beloved authors behind. But, now I nominate Des Traynor to take the baton and run. He has been known to read a few books, so I look forward to seeing his choices.’ I stopped at 25. As we are in the midst of another lockdown now, at least until the end of November, I’ve decided I’ll press on. Will I reach 30? 50? Most of my library is in storage still, which makes this a more difficult task, but I’ll see what I can do. Note: I didn’t adhere to the ‘no reviews’ stipulation.

A Roland Barthes Reader, edited by Susan Sontag, who did so much to popularise Barthes’ work in the Anglophone world. A compilation is the ideal introduction (although I’d previously enjoyed the accessible and witty Mythologies). Just look at the table of contents to get a flavour of the material covered in these essays:

Table of Contents

Writing Itself: On Roland Barthes by Susan Sontag p. vii

Part 1

On Gide and His Journal p. 3

The World of Wrestling p. 18

from Writing Degree Zero p. 31

The World as Object p. 62

Baudelaire's Theater p. 74

The Face of Garbo p. 82

Striptease p. 85

The Lady of the Camellias p. 89

Myth Today p. 93

The Last Happy Writer p. 150

Buffet Finishes Off New York p. 158

Tacitus and the Funerary Baroque p. 162

Part 2

from On Racine p. 169

Authors and Writers p. 185

The Photographic Message p. 194

The Imagination of the Sign p. 211

The Plates of the Encyclopedia p. 218

The Eiffel Tower p. 236

Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives p. 251

Flaubert and the Sentence p. 296

Lesson in Writing p. 305

Part 3

The Third Meaning p. 317

Fourier p. 334

Writers, Intellectuals, Teachers p. 378

from The Pleasure of the Text p. 404

from Roland Barthes p. 415

from A Lover's Discourse p. 426

Inaugural Lecture, College de France p. 457

Deliberation p. 479

My copy is covered in pencil underlinings – the sure sign of a riveting read. (George Steiner: “An intellectual is, quite simply, a human being who has a pencil in his or her hand when reading a book.”) ‘Flaubert and the Sentence’ is a particular favourite. (‘For Flaubert, the sentence is at once a unit of style, a unit of work, and a unit of life; it attracts the essential quality of his confidences as his work as a writer.’) But so are the extracts from The Pleasure of The Text and A Lover’s Discourse – which I went on to read in full, along with my own personal favourite, the last book he published before he died, Empire Of Signs.

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/10/books/books-of-the-times-020710.html

Saturday, 12 September 2020

Diana Rigg RIP

Here's a piece I wrote for The Irish Independent circa 1996. I remember at the time features editor Marianne Heron telling me that I needed to be more famous before I could start writing features like this. Hmmm.

The Avengers television series is exactly the same age I am, debuting in January 1961, and it has always held a special place in my affections. According to RTE’s autumn schedule yet another rerun is imminent, so it seems timely to ask: what is it about the programme that accounts for its continued and enduring appeal?

The Avengers began life as a vehicle for Ian Hendry, a popular actor whose own programme Police Surgeon was not proving to be a hit. His character, Dr David Keel, was aided by fellow investigator John Steed, played by Patrick Macnee, a mysterious undercover agent who became increasingly suave, wielding a steel-rimmed bowler hat and a brolly which hid a rapier. While the show started off as a crime thriller series with tough, gritty storylines, it found a new style after Hendry's departure, and the arrival of Honor Blackman's emancipated anthropologist Catherine Gale. I'm too young to remember her contribution (I was still in nappies), but my elders tell me the character stunned early sixties audiences with her stylish leather outfits and her ability to handle herself in a fight. The Avengers' popularity soared, and it became a ratings winner for ITV.

But it was with the arrival in 1965 of Blackman's replacement, Diana Rigg, as Mrs Emma Peel, the wife of a missing pilot, that the show first came to my childhood attention. Steed and Peel's adventures grew more bizarre than those which went before, as they encountered karate-chopping killer robots and vegetable monsters from space. The Rigg/Macnee episodes are the most oft-repeated and fondly remembered, typified by their inventive, sci-fi tinged storylines, their crazy villains and eccentric characters, and the intriguing, understated (but all the more powerful because of that) sexual chemistry between the two leads. The show was camp before anyone, except Oscar Wilde or Ronald Firbank, knew what camp meant, and it helped to extend the realms of fantasy fiction on the small screen. It is no coincidence that both Blackman and Rigg went on to star in what were at the time the most extravagant of latter day big screen fairytales, the Bond Movies, Blackman as Pussy Galore in Goldfinger, and Rigg as Contesse Teresa di Vicenzo in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (the only woman to ever get the action hero up the aisle).

On a personal level, what was it about Rigg's Mrs Peel that made her my four-year- old self's first screen goddess? Apart from the obvious fact that she was great looking, I must have figured that she was my kind of girl because when she wasn't busy beating up baddies without batting an eyelid, she was usually to be found relaxing by dipping into a hefty volume on astrophysics. She also seemed completely unruffled, no matter how big a jam she found herself in. When Rigg left the series in 1967, I sent her a card wishing her well for the future, and was rewarded with an autographed photograph in return.

After Rigg's departure, Macnee's new partner was Linda Thorson, a Canadian fresh out of drama school, who became Tara King. Now operating under orders from their crippled boss, Mother, the duo took on strange cases involving highly improbable threats to national security, but the show had passed its halcyon days for me and started to go downhill, and I began to lose interest.

The series was cancelled early in 1969 but was revived briefly for two seasons as The New Avengers in 1976 and 1977, when it reached its nadir. Macnee returned as Steed alongside Gareth Hunt as Mike Gambit, a younger man contrived to appeal to younger women, and Joanna Lumley as Purdey, a too traditionally feminine woman to cut it as an Avengers girl. Lumley has since proved, with Absolutely Fabulous, that her forte lies more in comedy. But as a product of the sixties, a decade it could be said it helped to define, The Avengers could not be rehashed to suit the seventies.

Aside from her stint as a Bond babe, Diana Rigg moved on to pursue a career as a 'serious' actress, playing Regan in the BBC's production of King Lear, and Lady Dedlock in their Bleak House. Most recently she has been in Ibsen's Master Builder and Brecht’s Mother Courage at the English National Theatre.

It was only as I got older that I realised my earliest object of screen desire, my first fantasy fodder, was actually more than 20 years my senior. But she's captured forever as she was then, pristine and timeless, in those at once innocent and knowing adventures with Macnee from the mid-sixties.

Now where did I put that photograph?